Starr, an incredibly cute 3 month old Pug, was the runt of her litter. She was not thriving and was not eating properly. So she had to be bottle-fed, every 2-3 hours, round the clock, by her amazingly dedicated owner!

When her siblings were transitioned to solid food, she couldn’t handle it.

After trials and errors, her (unbalanced) diet ended up being hamburger and goat milk.

Her family vet discovered the cause of her problems: Starr had a cleft palate.

The options offered were to euthanize her, or have surgery.

Starr’s owner comments: “Euthanasia was not even an option. She was a playful, lovable puppy full of energy and just needed a little help getting nourishment.”

So her owner reached out to Harrisburg Regional for help. I replied that I would be happy to help, and I would prefer waiting until she is at least 6 month old to increase the success rate of surgery.

The reason is that tissues become stronger as the puppy ages, which make them more likely to hold and heal properly.

It was not an easy wait… “Feeding her was scary at times, because she would spew milk from her nose if she drank too fast.”

After a few more encouraging emails to “hang in there for a little bit longer,” surgery was finally scheduled when Starr turned 6 months.

Her owner remembers: “The days leading up to her surgery were very stressful. I kept hoping we were doing the right thing for Starr. At the time of her surgery, she only weighed 6 lbs.”

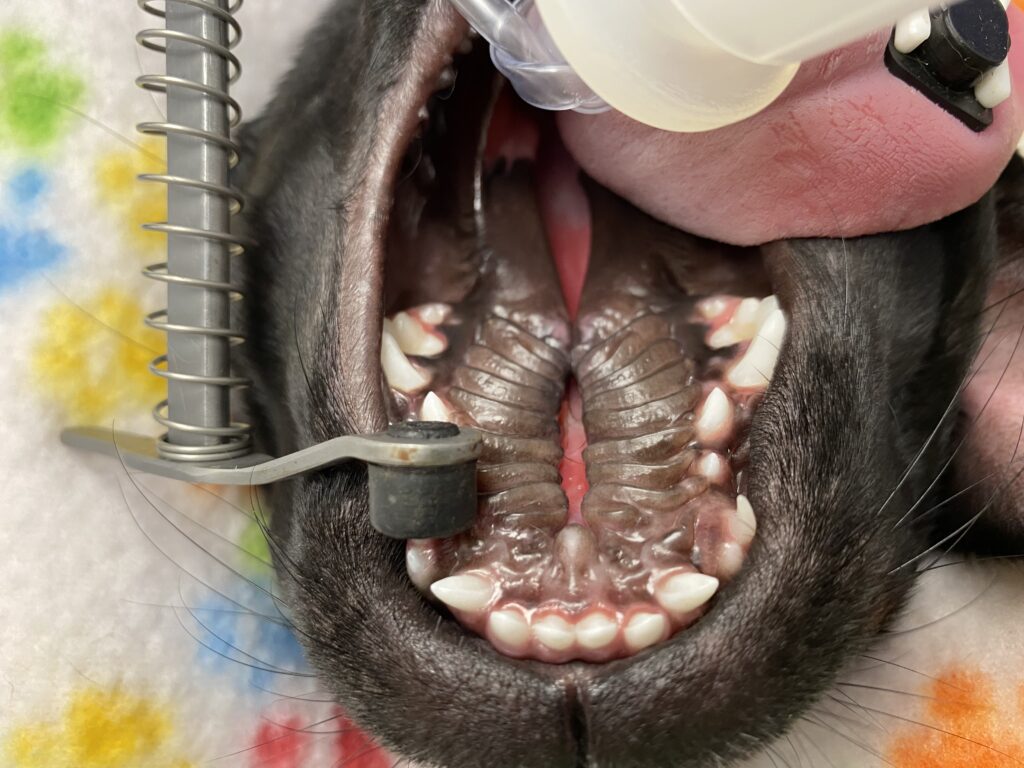

During the initial exam, awake, a cleft of the hard palate was confirmed. The hard palate is the front part of the roof of the mouth. It is hard because there is bone behind it.

Several drugs were given in order to make anesthesia safer, as is it riskier in patients with a flat face (Brachycephalic breeds including Pugs, all Bulldogs, Boston terriers etc.).

During a second exam, under general anesthesia, a full investigation revealed that there was also a cleft of the soft palate. The soft palate is the back of the roof of the mouth, where is no bone.

So Starr’s diagnosis was a severe, complete cleft palate.

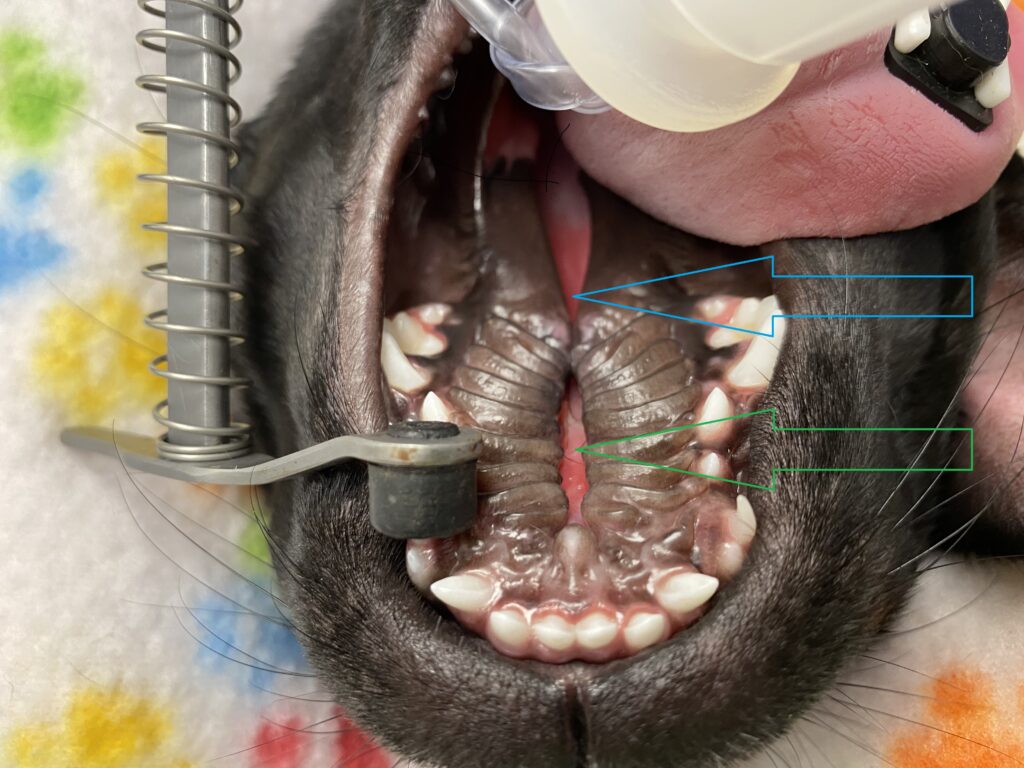

The picture below shows the roof of the mouth before surgery. The blue arrow points to the soft palate. The green arrow points to the hard palate.

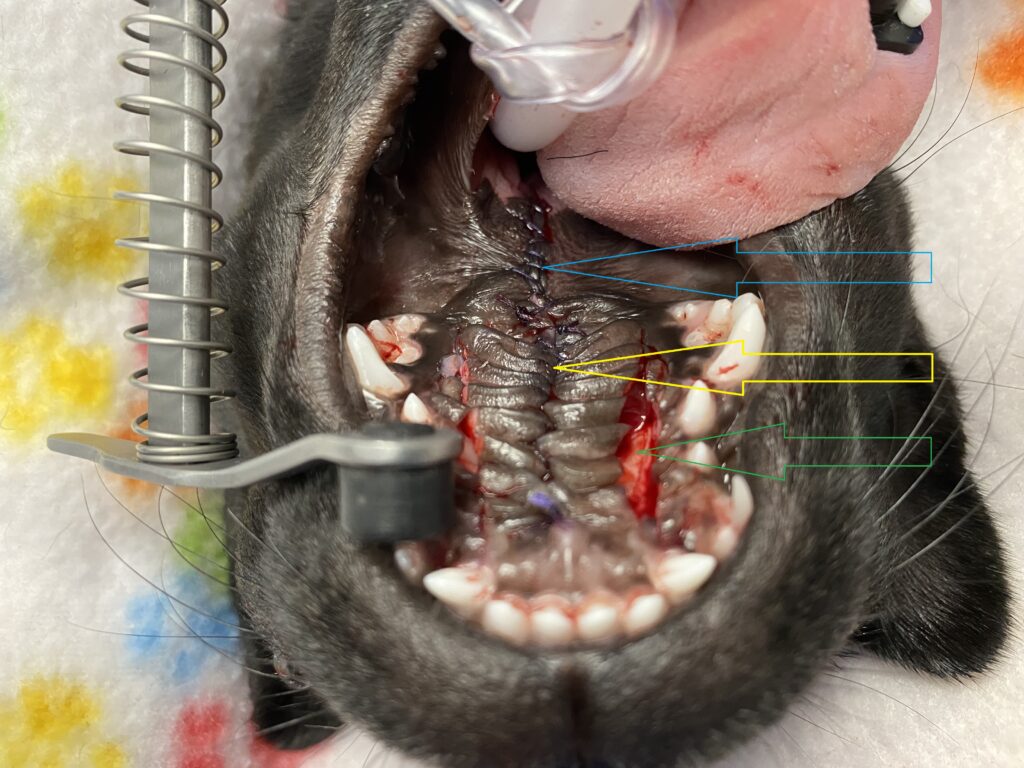

Surgery of the cleft of the soft palate involved suturing it in 2 different layers.

Surgery of the cleft of the hard palate was a bit more technical. It involves robbing tissue from Paul to pay Peter. In other words, a band of tissue (called a flap) was created on each side of the roof of the mouth. Once they were loose enough, they were sutured in 2 different layers (see blue arrow). This left an open area on each side, where bone is actually visible (see green arrow)! The mouth is (usually) an amazing healing machine, and new tissue covers the bone over time.

Starr did great through anesthesia and recovered smoothly.

The picture above shows the roof of the mouth after surgery. You can see the stitches in the middle (blue arrow for the soft palate, yellow arrow for the hard palate) and the exposed bone on either side (green arrow).

Starr went home to heal over 4 weeks. Instructions included strict rest, soft food and no chew toys to avoid damaging the repair.

Four weeks later, an exam under light sedation confirmed that everything had completely healed.

Starr could finally come out of confinement and live a normal life.

Starr’s owner concludes: “It was a long 4 weeks of confinement, but it was all worth it! She is now playing, eating and drinking from a bowl like nothing ever happened to her. Her surgery was successful. We couldn’t be more grateful. We are looking forward to loving Starr for many, many years.”

If you would like to learn how we can help your pet with safe surgery and anesthesia, please contact us through www.HRVSS.com

Never miss a blog by subscribing here: www.HRVSS.com/blog

Phil Zeltzman, DVM, DACVS, CVJ, Fear Free Certified